Duty & honor beyond the war

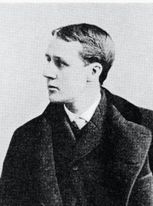

Major General Francis Channing Barlow resigned his commission in November, 1865 to pursue his legal career and political opportunities that were being presented to him. He went on to serve the state of New York as Secretary of State, US Marshall for the Southern District and Attorney General. His position as Attorney General was one he took much pride in. After his political career ended he remained in the public eye and continued his outspoken nature sitting on various committees generally where he felt wrongs needed to be made right where his ethical nature took precedence in discussions.

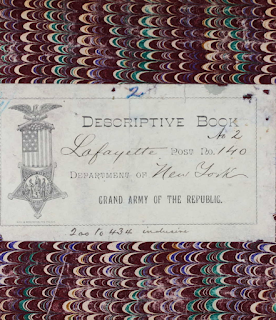

There are many examples that show his outspoken nature on many different topics, issues and corrupt practices. Even as his health began to fail in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s his voice and pen were strong. In 1890 The Disability Pensions Act was undergoing reform and was taking a lot of criticism from GAR members. Barlow included. He remained an active member of the Lafayette Post # 140 for his service in the 61st NY. Barlow was vehemently against the language of the change. His opinion on honor, bravery and duty carried over to his private life. Here he firmly states his opinion on the subject with respect to “stragglers” and “deserters.”

Now, it is well known that General Barlow’s discipline to motivate soldiers to face certain dangers and possible death had zero tolerance for the “straggler” and the “coward”. That opinion did not soften in the twenty-five years since the war ended. Barlow’s concern with how the act was written was the Dependent and Disability Pension Act provided a limited service pension for honorably discharged veterans with a minimum of 90days service for widows and their children without requiring service connection to disability or death.

An 1890 article in the Boston Evening Transcript, Barlow wrote “the American people should be eager to provide for the soldiers who fought its battles, if they were wounded, lost their health in the service and also to provide for the widows and minor children of those soldiers, who lost their lives…. No one can deny.”

He further writes, in true Barlow fashion, “Mortifying as it is, the truth requires it to be stated that there were cowards, stragglers and shirks in the army and we must admit that a considerable number of the men who are now ‘demanding’ pensions do not deserve them.” He wanted money to go to those that deserved it most. Those that did their duty and followed orders as instructed not to those that did not fight with honor but rather turned coward in the face of duty. He goes on to emphasize that no brave and faithful soldier shall suffer in his old age. Barlow recommended that Congress should establish “soldier’s homes for veterans who are poor and friendless in their old age but this a very different thing from this indiscriminate pensioning.”

Barlow advocated for those in need and wanted them to be treated fairly. Although Barlow did not speak much of his service after the Civil War, he was especially passionate about the care of veterans, as long as duty was upheld honorably. In his obituary it is noted that Barlow belonged to the Seventh Regiment National Guard and a member of their Veteran board after it was disbanded in 1890.

Frank never applied for a pension. Although wounded seriously twice, he certainly could have, but he felt he was able to work and was financially stable. Others less fortunate had a greater need.

ReplyDelete